Next time you are in Lucknow, the City of Nawabs, leave no stone unturned to get a taste of its rich history and culture.

By Rashima Nagpal

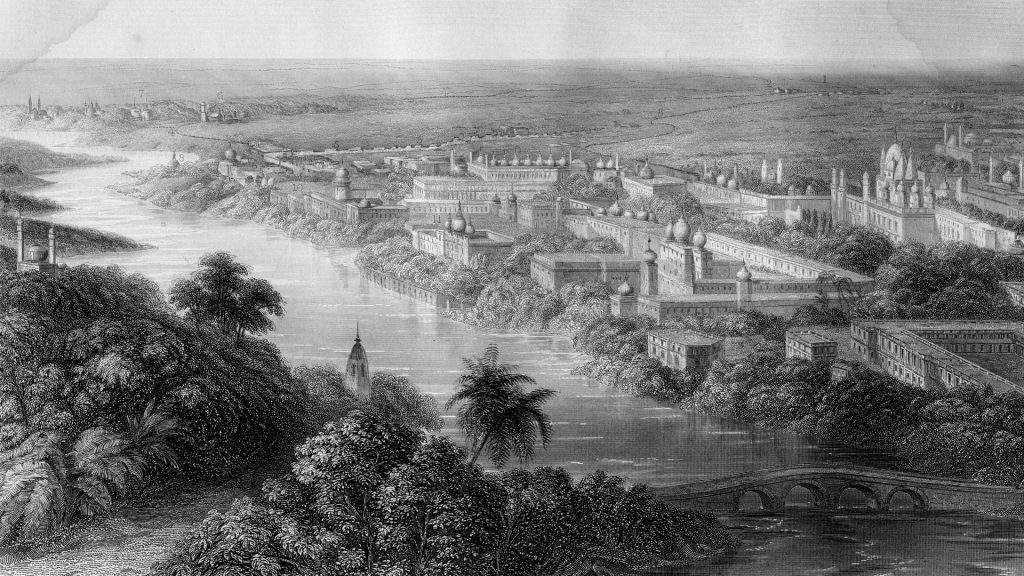

The Constantinople of India, Shiraz-I-Hind and the Golden City of the East are some of the glorious names given to the city Lucknow. A landmark city, Lucknow has played a pivotal role in India’s history. In the last 700 years, it has been the seat of many an erstwhile royal, as well as the centre of cultural and political movements. From the mighty Mughals to the Nawabs of Awadh, from the Viceroys and Persian invaders to the East India Company, different people brought in different nuances to the city. And, have thus left their legacy to shape the next.

Mythology, too, has played a role in shaping the cultural context of Lucknow. According to Hindu legend, Raja Ramchandra, after conquering Lanka, gifted this region to his brother Lakshman as a reward. Apparently, a village on a hillock overlooking a river became Lakshmanpur. Thus, the name Lucknow seems to be an anglicised derivative of the same old Lakshmanpur.

Walking through history

At some point in the 18th century, the nawabs, the nobility of Persian origin, decided to create a semi-independent state in Awadh. A trip to Lucknow is incomplete without experiencing a tale or two of their flamboyance. The fact that locals still talk about it tells of their indelible mark. And, what they built is relevant to date. The landmark monuments speak volumes about Lucknow’s identity. During the reign of Nawab Asaf-ul-Daulah (1775-1797) came the Bara Imambara. The Bhool Bhulaiya—a labyrinthine network of corridors with 489 identical doorways, positioned above the main hall—is a highlight. Likewise, the Chota Imambara is the Hussainabad Imambara. It is one of the greatest imambaras of the reign of Nawab Muhammad Ali Shah (1837-1842).

Built between 1775 and 1797 is the Rumi Darwaza. It has a cusp arch on the western side and three large openings formed by pointed arches. It features 13 small arches and is flanked by two arcaded wings on the eastern side. Farhat Baksh Kothi, the royal complex was designed by polymath Major General Claude Martin. He thus took French architecture to Lucknow, which was developed by Nawab Saadat Ali Khan. There was an emphasis on a wide road, almost two miles long, which started from the royal citadel, connecting to the former hunting lodge of Dilkusha Kothi. Therefore, a visit to the Dilkusha Kothi gives you a glimpse of a confluence of cultures. While at Kaiserbagh, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s grand address, a sequence of gateways are a typical architectural device. They hint at a celebration of power.

A rich legacy

In its heyday, the skyline of the town had Aurangzeb’s mosque on Lakshman Hill. And the countless imambaras that outnumbered the mosques, and the karbalas, whose minarets towered above the tightly-packed Lucknow. Although conventionally associated with the martyrdom of heroes, the imambaras in Lucknow simply served to celebrate the warrior identity. Thus, they gained significance among the Rajputs who were known for their loyalty towards the Nawabs.

This confluence is present in the imambaras’ architecture. It, therefore, features nuances of both Mughal and Rajput aesthetics. Unlike the imambaras, the karbalas did not find inspiration from either model. Their architecture takes inspiration from the Persian rauzas. It represents the battlefield of Karbala and the burial places of Hasan and Husain in Iraq. Their features resemble the Iranian and Iraqi prototypes. Think plain façades, minarets with balconies, the domed vault of the central shrine decorated with stars. Thus emphasising meditation and solitude.

Living the culture

Between the Persians and the Nawabs of Awadh, Lucknow transformed into a flourishing centre for the arts. With lavish patronage to prose and poetry. Therefore the quintessential Lucknawi tehzeeb that we admire today is due to the beauty of the Urdu language and how it bloomed in the region. The rulers believed in the power of poetry. Their customs, their mannerisms, their etiquette, their grand traditions, were all underlined by the effusive use of this mellifluous language.

Towards the end of the 18th century, when matters in the courts of Delhi got tense, the likes of courtly poets and artists migrated. Many of them turned to Lucknow, where locals took a keen interest in them. No wonder the city emerged with Dabistan-e-Lakhnau, a scholarly sect of its own. Artists such as Hasrat Mohani, Ameer Minai, Begum Akhtar and Meer Taqi Meer, to name a few. Thus the literati would go on to tell you about the age-old understanding. That accords the revered ghazal tradition into Dabistan-e-Dehli and Dabistan-e-Lakhnau or the Delhi and Lucknow schools, respectively.

This migration of artists from Delhi made way for another art form that is now intrinsic to Lucknow: kathak. Home to this Indian dance form that incorporates music with storytelling, the Lucknow gharana is one of the three major schools of kathak. Vivid pictures of Lucknow painted by Premchand as the president of the Progressive Writers Association, Satyajit Ray in his film Shatranj ke Khiladi. And Muzaffar Ali and his Umrao Jaan set against the backdrop of aristocratic Awadh are all, therefore, testament to the city’s cultural significance.

Contemporary scenario

Here’s a pro tip: Keep an eye out for the next edition of the Lucknow Literature Festival (lucknowliteraryfestival.com). It is a one-of-a-kind festival that sees mushaira and kavi sammelan come together. For an interpersonal experience of art in the city, one of the must-visits is the Hussainabad Picture Gallery. It is one of the oldest picture galleries in the city. It was founded by Nawab Mohammad Ali Shah (the third Nawab of Awadh) in the year 1838. Housed in a beautiful terracotta building with wide verandas on both sides, it preserves some rare life-size portraits of the Nawabs. Stories say that these paintings were made on elephant skin. The colour came from diamonds. It also has a mosque and a pond in front of it, which add to the delight of being there.

Now most people who visit Lucknow do not return without buying its signature embroidery called chikankari. But not many would know that its origin goes back to the intricate carving patterns in Mughal architecture. They are still visible across the city. Today, there are close to 5,000 families involved in this art form, in and around the villages of Lucknow. Thus, in the treasure trove that is this city, some gems are still waiting to be explored. Seek and maybe you will find them.